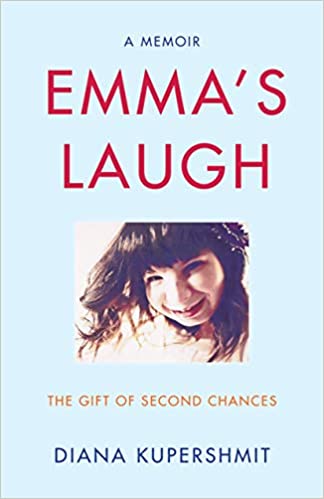

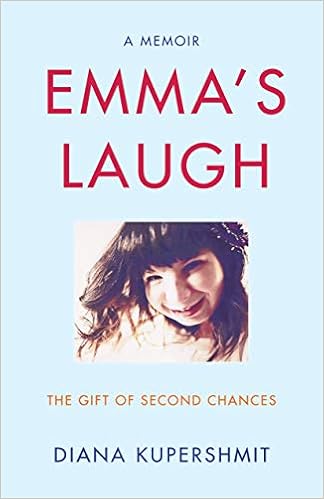

The world of motherhood can be lonely, even more so when you are parenting a child with a rare disability. Yet, when I met Diana Kupershmit, we found an immediate interception of our worlds as writers and mothers. Her memoir, Emma’s Laugh: The Gift of Second Chances, debuted this month with incredible reviews. This incredible story of her daughter, discusses the unimaginable side of parenthood with grace, humor, and love.

This is a must read. Her writing inspires changes. Her story promotes community. Her memoir creates a legacy for her child.

I had the opportunity to speak with Diana about her writing process and her thoughts on being a parent to a child with a disability.

I have found writing has been my lifeline to make sense of the struggles of my family. What inspired you to write Emma’s Laugh?

I never aspired to write a book, certainly not about losing a child, but when Emma passed, I found myself putting words down to make sense of the loss and as a form of grieving, I suppose. I found it healing, so I continued doing it. When readers in my writing class began responding positively to my words, it gave me the confidence to continue, until I found myself with a first draft.

What advice would you give to another writer?

Don’t wait for permission to write. For the longest time, I felt like an imposter while writing my memoir, because I didn’t have a background in writing, an MFA after my name. I was a voracious reader though, always. I would be that kid, even in high school, walking home with a book in my hand—reading. In college and graduate school, I would occasionally scribble feverishly all my existential angst, when things got dark when my social anxiety swallowed me whole. But then the clouds would pass and I would put the pen down until the next episode.

Once, I came close to getting an essay published in my university paper, which my writing workshop professor submitted, but alas, it didn’t make it to print. This is all to say, that when asked about my memoir, I always offer a disclaimer—that I’m not a writer, I’m an author, and a reluctant and accidental one at that. My perfectionist tendencies dictated that I be if not brilliant, then at least adept, in all my undertakings, and without the history or credentials, I needed to educate myself on the craft. So, I signed up for a writing workshop, or ten, and I read all the memoirs I could get my hands on. Only now, I call myself a writer, because as someone once told me, you are what you do—and I wrote many, many words. Diane Cameron says that insecurity rides along with authority, so I guess I’m on the right track.

One of the reasons I love your memoir is that it provides an authentic look at the day-to-day life of someone raising a child with a disability. Books like this help to fight against the stigmas facing so many of our children and foster empathy for other families. What do you wish you knew before having a child with special needs?

Life wouldn’t be dark, insular, and burdensome. I wish I knew that there were social support systems in place for kids with special needs—therapies, school, home-care nurses, other families. I wish I knew that Emma’s life would not be considered a tragedy to be pitied and marginalized and that I would be forced to live alongside what I believed would be a sad existence for all in her sphere. I wish I knew the gifts that special needs kids bring with them if you’re open to seeing them with a generous heart—the gift of unconditional love and acceptance, among many others. I wish I knew that Emma would teach me the indelible lesson of self-acceptance and by extension, self-love, just by example. I wish I believed enough in myself and saw past society’s ableist message. Maybe then I wouldn’t have given her up for adoption for those five months. But then again, I wonder had we not had this misstep, detour as I call it, would we have had the gift of knowing life with and without her, and choosing the former.

You tell your story with so much honesty and vulnerability. What authors/stories have inspired you to find this courage to tell your own story?

Some of the memoirs I came across in my readings that have influenced me were written by mothers like me who lost children. Emily Rapp Black writes poignantly and heart-wrenchingly beautifully about losing her son to Tay Sachs, in The Still Point of the Turning World. Monica Wesolowska in her touching memoir, Holding Silvan, writes about her son who lived for only a month. Knowing Jesse, A Mother’s Story of Grief, Grace, and Everyday Bliss, by Marianne Leona, chronicles eighteen years with her special needs son. This last memoir is the closest to mine in experience, in terms of how long we had Emma with us before we lost her. I was fortunate to have Emily Rapp Black and Monica Wesolowska blurb my book. It was humbling and validating.

5. There are so many moments where your humor and personality shine through, even during difficult circumstances (My personal favorite: “Today’s Sesame Street program is brought to you by the letter V for vesicostomy). Was this intentional in your writing or something that naturally came out as you developed your writing voice?

My sense of humor always saved me I believe. My dad is a jokester and I’d like to think I inherited his humor gene. There’s an expression—comedy is tragedy plus time. I waited 6 months or so before I started writing and that space of time was important in establishing enough distance to view the events of so many years ago, when she was first born, with a less grief-tainted lens. Though I was in the midst of my second wave of grief, having lost Emma, the first grief experience—grieving the loss of the dream of a healthy baby, grieving the loss of the life I imagined for her and myself when she was first born, was relatively speaking, less annihilating, because I was in a position of having had eighteen glorious years with her. Emma lived her life with levity, her laugh silent but lung-emptying. I wanted the book to reflect the way she taught me to be in the world—finding beauty, humor, the love in all things.

Emma’s Laugh: The Gift of Second Chances can be purchased here.